What is and is not allowed when using lookalikes in advertisements? In the case between Verstappen and PICNIC, the Court examined the boundaries between portrait rights and commercial interests.

The use of lookalikes in advertisements is increasingly raising legal questions. In the case between Max Verstappen and PICNIC, the court decided that there was no violation of portrait rights or unlawful conduct. This ruling calls into question the boundaries of portrait protection and commercial interests.

Context of the case

Max Verstappen, the Dutch Formula 1 pride, occasionally appears in commercials for Jumbo. In 2016, Verstappen raced in a Jumbo advert in his race car to deliver groceries at lightning speed.

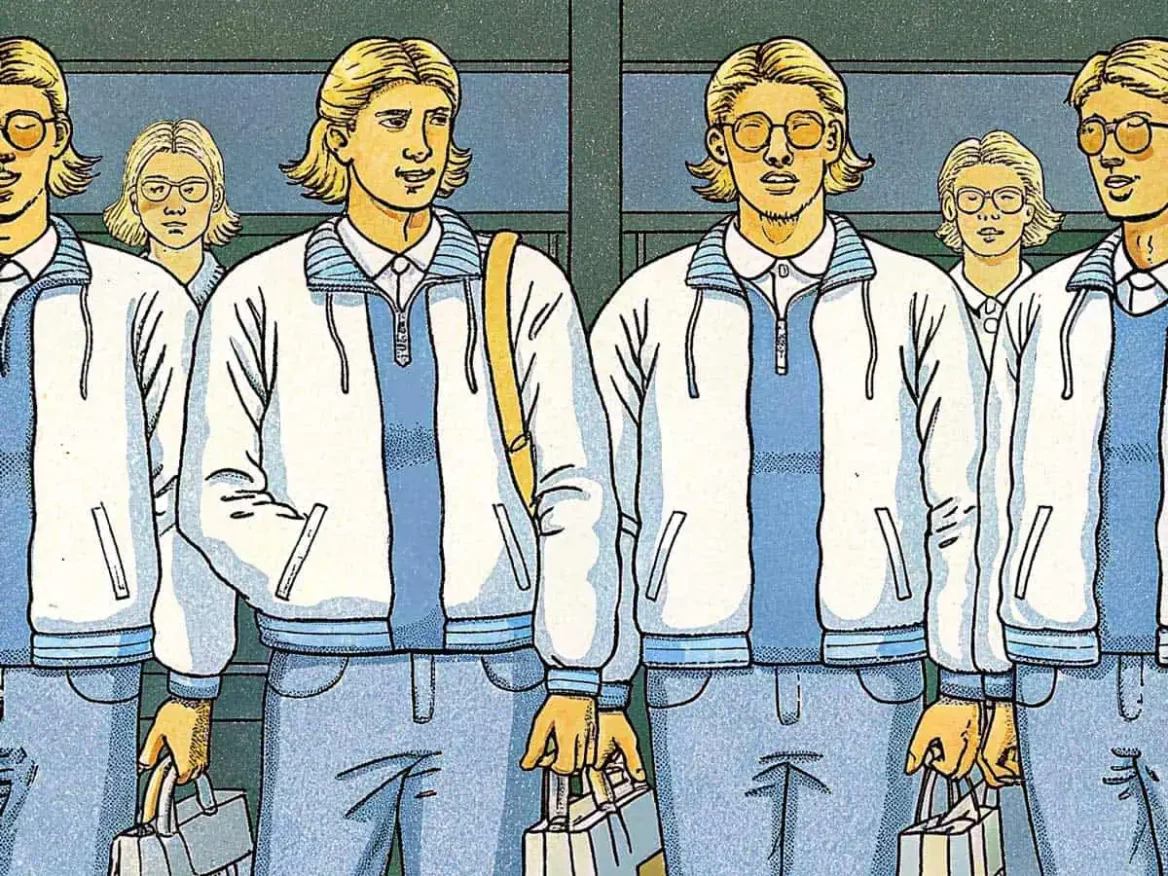

Soon after, PICNIC posted an advertising video on Facebook of a lookalike of Verstappen. The lookalike calmly delivers groceries with the famous PICNIC van.

Violation of portrait rights

Verstappen sued PICNIC, alleging PICNIC violated his portrait rights and acted unlawfully towards Verstappen. The court found in his favour.

The court disagreed, ruling that there was neither violation of portrait rights nor tort.

Portrait law protects against the use of unauthorised disclosure of a person’s portrait. The court ruled that PICNIC’s depiction on film of the actor who played Verstappen (the “lookalike”) could not be seen as a portrait of Verstappen.

Performance persiflage

It would be a persiflage of Verstappen’s appearance in the advertisements for Jumbo. Portrait rights do not extend to protection against visual material in which certain features of someone’s appearance are depicted or imitated by another person, if there is no reasonable doubt that it is not that person, but merely a lookalike.

This applies even if the association is intentionally created. In this case, this means that portrait rights provide no comfort for Verstappen to counter the PICNIC advertising.

However, there may be a tort if Verstappen’s honour and reputation are harmed or business interests are damaged by their publication. According to the Court, this is not the case with the PICNIC films.

No diffarming expression

The advertising is not seen as diffusing expression. According to the Court, if there is no confusion regarding the identity of the two persons involved, it is hard to see that – just because a well-known person has a redeemable popularity – this immediately means that imitating that person would be unlawful.

This is true even if the person who posted the video has a commercial interest in doing so as a result of the huge attention the video has received.

Reasonable cost

After all, PICNIC saves reasonable costs by not paying for the real Verstappen and still gets a lot of attention.

For unlawfulness, additional circumstances are then necessary, the court said. The fact that Jumbo, as the party that contracted Verstappen for advertising purposes, could successfully oppose such imitation does not make the expression unlawful towards Verstappen. In this case, Jumbo ‘saw the humour in it’, and that is the end of the matter for Verstappen’s claims.

Interesting according to Good Law

What is interesting in this ruling is, among other things, that the Court indicates that because of the distance observed from Verstappen’s true person and activities, it cannot be assumed that as a result of the PICNIC video on Facebook, Verstappen will be associated with PICNIC’s activities or that Verstappen would support PICNIC’s services.

All the more so, according to the court, because the average viewer sees the PICNIC clip as a persiflage of his performance in the Jumbo commercials. It can well be argued that whether a viewer sees Verstappen or a lookalike depends on whether a viewer is familiar with the Jumbo commercials.

If viewers don’t know those commercials, an average viewer may actually think it is Verstappen. The PICNIC film is therefore not a persiflage of the Jumbo commercials, without having knowledge of those commercials.

In any case, such an average viewer might think there is a collaboration between Verstappen and PICNIC. There is a good chance, with more video-on-demand services being watched and less television, that the internet generation among us did not know about the Jumbo movies.

With that, let me at least speak for myself. So the fact that this clip was a persiflage of Verstappen in Jumbo’s commercial and that there is no confusion between the lookalike and Verstappen is not at all obvious.

Lookalike of Katja Schuurman

In 2005, the Breda District Court ruled on the use in an advertisement of a lookalike of Katja Schuurman that preventing the use of Katja Schuurman’s ‘just-not-quite-portrait’ did in fact constitute a reasonable interest of portrait rights.

So if Verstappen’s lookalike was precisely a “just-not portrait” of Verstappen, especially when we know that a large proportion of viewers would make little or no difference between lookalike and Verstappen, can Verstappen successfully invoke portrait rights?

Edgar Davids case

With regard to the considerations of the ‘Edgar Davids’ case in 2017, the Verstappen judgment also seems to be a turning point. In 2017, the Amsterdam District Court ruled that the Edgar Davids-inspired avatar in the game League of Legends was an infringement of Davids’ portrait right.

The issue, according to the court, was whether the person could be recognised in the portrait. The (online) public recognised Davids in the avatar and elements of the avatar and the appearance of Davids were sufficiently similar to say that the image was a portrait. In the PICNIC video, Verstappen is clearly recognisable by the lookalike’s appearance and the audience thinks the same.

The difference with these cases seems to be the ‘humorous’ edge of the PICNIC clip. Humour, however, does not make a Davids-inspired avatar or Verstappen lookalike suddenly less close to their portrait.

A real risk to the known person

The use of lookalikes of famous people, regardless of whether contract parties can see the humour in this as Jumbo sports does, creates a real risk for the famous person that his exclusivity will be taken away in a next round of negotiations for advertisements or other commercial expressions.

The casual use of lookalikes to get more views and attention in commercial statements dramatically changes the commercial position of a famous person.

If an Instagram influencer uses a Venus razor, can I ‘persiflate’ her by making a comic video in which I imitate her and use Gillette? Or is that going too far?

And a YouTube vlogger who has a partnership with, say, Apple, can I persiflage that with Samsung or Huawei? The commercial stakes are high and the boundaries are not (yet) well defined. It remains to be seen what this ruling will mean for those whose work depends on their commercial position.