On December 4th, 2025, the Court of Justice of the EU handed down its long-awaited judgment in the joined cases Mio (C-580/23) and Konektra (C-795/23).

The judgment is part of a series of rulings on the copyright (and/or design right) protection of works of applied art and aims to provide further clarity on both the assumption of copyright protection and – for the first time so explicitly – the assessment of infringement.

However, does the Court offer more legal certainty with new formulations, or are familiar problems simply being couched in new terms?

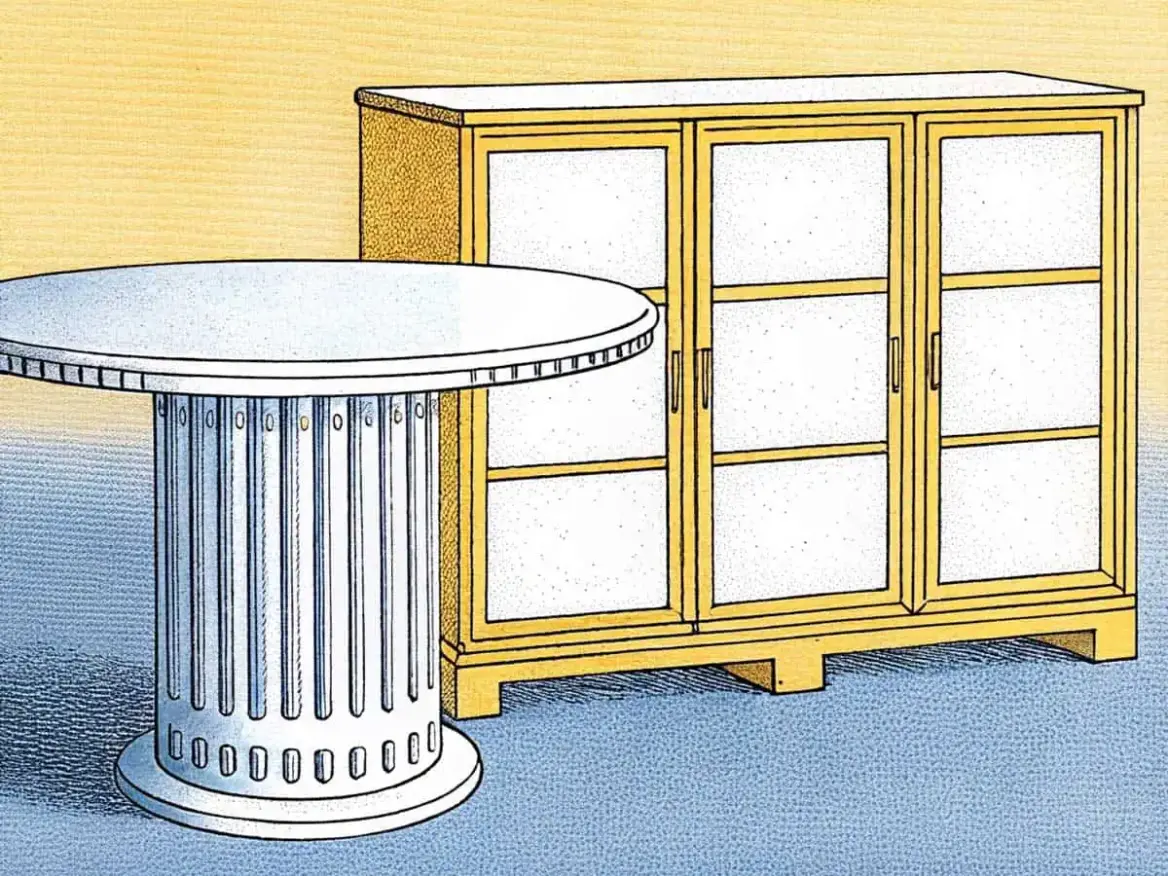

The background: utensils

Both cases take place in the furniture world. Mio concerns a copy of a designer table; Konektra focuses on the iconic modular furniture system USM Haller.

The national courts referred questions for a preliminary ruling on (i) the relationship between copyright and design rights, (ii) the interpretation of the originality criterion in applied art, and (iii) the standard for copyright infringement.

Opinions on these questions vary across Europe. In Germany, the long-standing doctrine was that utensils should be subject to a stricter test before copyright protection could be assumed. In the Netherlands and Denmark, for example, infringement occurs when there is a corresponding overall impression.

The Court decided to hear the cases together, resulting in a judgment with a clear systematic structure: first protection, then infringement.

1. Copyright protection: personality and creative choices

No higher threshold

The Court first of all dispels the idea that applied art is subject to a stricter copyright protection threshold than other works.

New formulation of the originality criterion

The Court reiterates that a work is protected by copyright if it constitutes an intellectual creation in its own right, but explicitly qualifies this with two concepts in the case of applied art:

- the work must express the personality of the creator, and

- this is achieved through the creator having made free and creative choices.

This wording sounds more precise than it actually is. The Court emphasizes that not every free choice is creative and that, in the case of utility objects, it cannot be assumed that design choices are automatically creative. The national court must therefore examine specifically which choices are not purely technical or functional.

At the same time, it remains unclear when a choice is creative and when a design actually reflects the personality of the creator. Is this due to the form, proportions, combinations, level of detail, or the totality of choices? The Court does not define this and explicitly leaves that assessment to the national court.

An original work does not therefore have to be new or unique in relation to existing creations. An original work must express the personality of the creator through free and creative choices.

Aesthetics are not enough

It is also important that the Court makes a clear distinction between aesthetics and originality. The fact that an object has a striking or artistic visual effect is not sufficient. Even a “beautiful” or distinctive design may remain unprotected by copyright if it does not express creative choices that reflect the personality of the creator.

In assessing originality, the type of work must be taken into account. Applied art is often limited by, for example, technical or ergonomic choices, or standards within the sector. Choices that are solely motivated by these factors are not original, unless these limitations do not prevent the creator from making free and creative choices within them and expressing these in the work.

Additional factors—such as inspiration, the author’s intention during the creative process, the use of common models, or recognition in professional circles—can at most be supportive but are “neither necessary nor decisive.”

It is therefore a question of all the circumstances of the case.

No automatic connection with design rights

Finally, the Court warns that copyright and design rights must be assessed strictly separately. The two regimes have different purposes.

Design rights and copyright apply different criteria:

- design right: objective assessment of the overall visual impression;

- copyright: subjective assessment of the link between the creator and the work.

There is no hierarchy and no automatic link between the two regimes.

Therefore, utensils such as furniture can be protected by both copyright and design rights if the conditions of both regimes are met.

2. Infringement: departure from the overall impression

A change of course

The part of the judgment concerning the infringement test is new. For the first time, the Court has spoken out explicitly against using a comparison based on the overall visual impression. According to the Court, this criterion belongs in design law and is unsuitable for assessing copyright infringement.

This seems to undermine the validity of the overall impression criterion commonly used in Dutch case law, at least for copyright disputes concerning applied art.

Recognizable adoption of protected elements

According to the Court, the correct test is whether:

- copyright-protected elements have been identified (elements that reflect the creative choices and personality of the creator), and

- these elements have been copied without permission and in a recognizable manner.

The Court refers to Pelham (July 29, 2019, C-476/17): even a small part of a copyright-protected work can constitute infringement, provided that part remains recognizable and reflects the creator’s own intellectual creation.

However, what exactly “recognizable” means in the context of three-dimensional utensils remains unclear. Should recognizability be assessed from the perspective of the average user, the professional, or the judge? And how does this relate to the fact that creative freedom is often limited in applied art?

No role for the degree of originality

The Court explicitly rejects the idea that the scope of protection would depend on the degree of originality or creative freedom.

Once a work qualifies as copyright-protected, it enjoys the same protection as any other work.

Independent creation as a relevant defence

Finally, the Court confirms that infringement presupposes borrowing. The defence that an alleged infringer has created something original (independently, without knowledge of the work) is valid but only plays a role in the question of infringement, not in the assessment of originality. The burden of proof rests with the defendant, for example by submitting documentation of their own design process.

So: more analytical, but not clearer

The Mio/ Konektra ruling undeniably provides structure: a strict separation between copyright and design rights, a sharper focus on creative choices, and a fundamental departure from the overall impression in cases of infringement.

At the same time, the Court replaces familiar – albeit criticized – criteria with new open standards. Concepts such as “expressing personality,” “creative choice,” and “recognizable adoption” are normatively charged and leave room for divergent interpretations.

The judgment therefore forces national courts to conduct a more detailed and explicit analysis but does not guarantee greater predictability. The main benefit is likely to be better reasoning, rather than unambiguous outcomes. The coming years will show whether this new terminology leads to greater consistency in case law or merely to new variations on the same fundamental discussion.